Sustainable Water: Reaching Net Zero

by Timothy L. Faulkner

April 2011

The most critical resource that will challenge military installations’ sustainability in the 21st century is water. Once thought of as a problem western states faced, it now has become critical to the survivability to the entire United States and nations worldwide. According to the U.S. Government, 36 states will face a water shortage in the next five years. (Associated Press, 2007) The vulnerability of military installations is a key concern of the U.S. Army and presents a particular challenge to military installation sustainability. Military installations and operations throughout the nation and around the world are already subject to water resource issues to include water supply adequacy, water quality, cost of delivery, and competition with ecosystem water needs (Jenicek, et.al, 2009). In fact, one of the goals of the 2005 Base Realignment and Closure was to have fewer but more sustainable installations worldwide. At the bedrock of sustainable installations are the requisite efficiencies needed to sustain our Army. Barry Nelson, a senior policy analyst with the National Resources Defense Council stated that “The last century was the century of water engineering. The next century is going to have to be the century of water efficiency.” (Energy Bulletin, 2010).

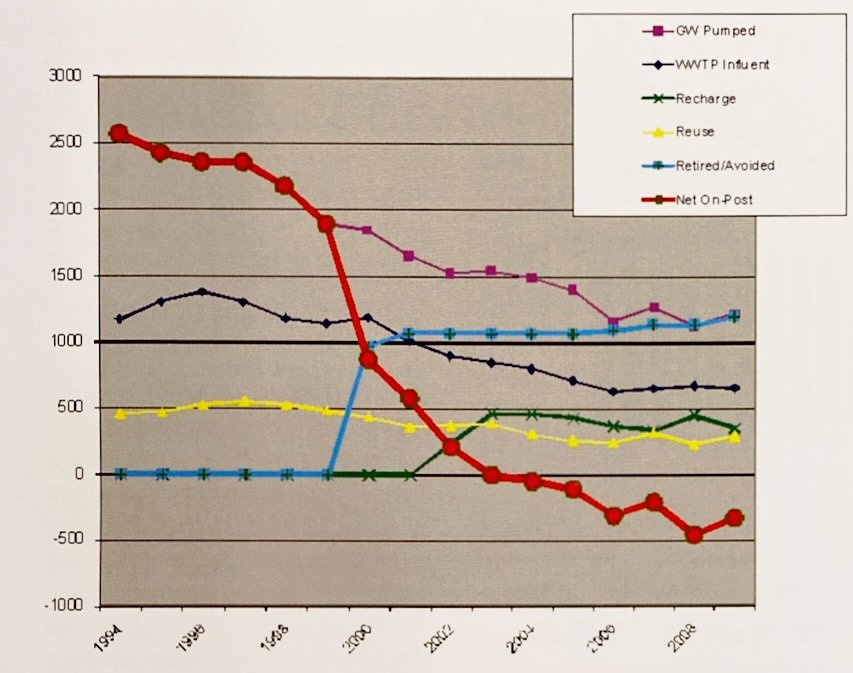

Fort Huachuca is a high desert post that has faced water resource challenges for more than a decade. The water efficiencies gained from 1989 to 2010 reduced the fort’s water pumping by more than 60 percent, from 3207 acre feet per year to 1142, even as the installation’s employee population increased by more than 30 percent. Synonymous with water pumping is the energy savings that are afforded to an installation. Other conservation efforts have brought the installation to a net zero impact on the regional aquifer, meaning that the installation replaces as much or more water than it uses. These results have brought the installation to the forefront of water sustainability within the Department of Defense (DoD), garnered the President’s White House Closing the Circle Award for Sustainability, and has allowed the fort to secure its role in supporting the warfighter.

Fort Huachuca is in southeastern Arizona, near the U.S./Mexico border and typically receives 15 inches of rain per year. Groundwater within the watershed not only supports perennial flow in the San Pedro River but also supplies our community of approximately 78,000 residents with their potable water. The U.S. Army Garrison, Fort Huachuca (USAG-HUA) knew that a holistic water management system, combined with a long-range plan for water sustainability could make it possible for an installation to zero-balance their impact on the regional water source. Planning, processes, technology, projects, and transformation thinking by leaders and installation personnel are required to meet this challenge. Recognizing the need to minimize impacts to the region’s water resources, USAG-HUA implemented a Groundwater Resources Management System (GRMS) and water resource management plan with a variety of strategies to improve water use efficiency both on and off-post. The Community Covenant approach to solving a regional issue was instrumental to make the necessary gains in water efficiencies.

The GRMS is an effective and systematic process that manages multiple aspects of the fort’s groundwater and its associated uses. The fort’s GRMS program includes a management plan, goals, measures, community education, and feedback. The approach addresses legal requirements, Army goals and requirements, management of shared resources, and societal responsibilities in the broader community. Elements of the process include conservation, efficiency, command policy, education, technology development, resource recovery and reuse, community outreach outside the fort boundary, and partnerships with non-profit organizations. The community outreach serves a dual purpose in the fact that is supports the Community Covenant and supports regional planning efforts in a greater watershed.

Standard thinking is that water is a limitless commodity of negligible cost, which leads to the perception of minimal value.

The 2009 garrison strategic plan Line of Effort (LOE) #6, Sustainability, mirrors the Installation Management Campaign Plan (IMCP) LOE #6, Energy Efficiency and Security. This practice of strict groundwater resource management directly relates to Key to Success EN 1 — Reduction of Energy and Water Consumption. Managing groundwater is imperative to our ability to provide resources, services, and infrastructure to our customers. Failure to protect this limited critical resource has direct implications on our ability to support ARFORGEN, our tenant organizations, and our installation partners. The broader impact on DOD was the fact that Fort Huachuca is home to 1000 square miles of restricted air space and 2600 square miles of Joint Command, Control, Communications, Computers, Intelligence, Surveillance, Reconnaissance (C4ISR) test range that supports Unmanned Aircraft System (UAS) and Counter Improvised Explosive Device (IED) efforts. This process is required to sustain personnel and missions on post by providing high quality potable water in amounts needed, but with minimal waste. By reducing waste, we also conserve the energy needed to pump water from 500 feet below the ground. Therefore, our water mitigation efforts decrease annual energy costs due to water no longer needing to be pumped from depth. The annual energy savings for pumping 410 million gallons less in FY 10 than the original baseline was more than $2 million.

Transformation in thinking is one of the key ingredients to starting water sustainment. Three major changes in thinking are: perception of water as a limited and valuable resource, cost benefit analyses that reflect that value, and education at all levels to spread this way of thinking. Without these critical ingredients, garrisons will struggle to change behaviors, rethink water cost, and redirect sustainment planning.

The garrison and Senior Commanders must lead a community-wide change in how we think about water. The transformation of thought is about how personnel, especially on post, perceive water. Standard thinking is that water is a limitless commodity of negligible cost, which leads to the perception of minimal value. From this perception, we do not question water use, why we are using it and whether the function using water can be accomplished with less or no water. Transformation thinking makes the presence of waterless urinals a given, and the sight of a flush urinal unconscionable. This one simple change saves us 25 million gallons of water annually. This perception transformation is particularly important to the Directorate of Public Works (DPW) personnel, especially the engineers and engineer technicians who will be responsible to find and implement the changes.

The second transformation, cost-benefit analysis, in thinking is also important to the process. It ‘breaks the code’ on the true value of conservation. Standard cost-benefit analyses for water-related practices are usually based on a fragment of the ‘cradle to grave’ cycle of water management. We overcame this by determining the full cost of water use. It includes all these cost elements: the commodity, pumping, potability treatment, distribution, waste water collection, wastewater treatment, wastewater disposal, and the often overlooked cost, commodity replenishment for any water consumed. All these costs must include the cost of energy as well as personnel and infrastructure. Once the true cost to the installation is understood, many additional technologies become cost effective. Using this methodology, the water management team made three lists, all calculated to compare cost per 1,000 gallons of water use. Projects were selected for funding based on the highest water yield for the funding available. Treated effluent reuse started making good economic sense. Technology implementation such as 1.5 gallon per minute (gpm) showerheads, dual flush toilets, and horizontal axis washing machines become extremely cost effective based on this full accounting of the cost of water. Some of these had payback periods of less than one year.

Through the continuous education, innovation, and application of multiple methods, we have grown mission and population while reducing our use of a critical resource.

The third transformation in thinking is led by installation leadership, from the top down. The imperative that was water management and conservation is as important as other cost savings and training measures must be measured and modeled by leadership. It becomes a part of the quarterly leadership briefs to all tenants. Articles are written, meters installed, and report cards issued. Pride in accomplishment and leadership accelerates a change in action. Water is serious business for Soldier and Family support and leaders understand progress in their efforts will garner more new conservation technology for their units.

The four pillars of the program implementation are education, conservation, reuse, and recharge. Water is measured at the well-head, at points of recharge and diversion for reuse, so all consumption and waste are included in the accounting. The GRMS maximizes the beneficial use and reuse of water, and minimizes waste from leaks and poor practices.

Through the continuous education, innovation, and application of multiple methods, we have grown mission and population while reducing our use of a critical resource. The policy and technology implementations in the plan can be easily exported to and implemented at other installations, based on what they can afford or are willing to put into policy. For example, the installation’s irrigation policy cost almost nothing to implement, yet reduced pumping by 10 percent, or more than 300 acre feet (97 million gallons) per year. The accompanying energy cost savings at Fort Huachuca, for just this policy implementation, using today’s electrical rates, is approximately $500,000 per year. Included in this policy was a prohibition on irrigating with unattended hoses. Violation of this policy carries serious consequences for repeat offenders. No longer will high installation water bills be the price for ‘yard of the month’ competitions.

Low cost efficiencies are the low hanging fruit that every commander can cultivate with little investment. The first area to attack in the short term was technology implementation. Much of the water used on post is for personal hygiene, showers, and toilets. Inexpensive adaptations include the change to 1.5 gpm shower heads, 1.5 gpm faucet aerators, dual flush toilets, and waterless urinals. These can be installed as funding permits and when fully implemented can reduce your water bill by 20 to 25 percent.

As these new devices are implemented, the education aspect alerts personnel to both the new fixtures and the reasons why. Additional tips are taught through education programs and command information venues. The USAG-HUA WaterWise-Energy Smart conservation education improves conservation awareness and actions among all demographics on the fort. The off-post community had a “WaterWise” program provided through the University of Arizona Cooperative Extension. Because the basic elements of our need were covered by the program, we contracted with the University to make some changes to the program for use on post, and added the energy conservation element. The Water-Wise Energy Smart program includes elements from water and energy checklists for quarters and administration buildings, to facility conservation audits and children’s programs through youth services. The program stressed doing the right thing, saving the installation money and the high desert location of the installation. When residents and employees understand why the urinals are waterless, why there are strictly enforced lawn-watering hours, and why they cannot hold limitless fundraising car washes on post, they accept and become part of the process — often reporting the broken values or running water themselves.

Longer-time horizon projects must also be planned and executed. Other specific reduction measures include: demolition of more than a million square feet of old, leaky facilities and infrastructure; leak detection and repair or replacement of pipes; installation of artificial turf; broad implementation of low-flow technology such as horizontal axis washing machines and replacement with evaporative coolers with refrigerated air conditioning. Waste water is treated to EPA Class B or B+ quality and used to irrigate the golf course and some landscaping. Remaining treated effluent is recharged into the aquifer. Other recharge on post includes several rainwater basins. Artificial turf has the ancillary benefit of saving grass maintenance, fuel cost and provides the Soldiers the great hand to hand combat training areas with the proper cushioning.

Fort Huachuca operates its own wastewater treatment plant producing a high quality effluent that has been used for irrigating its golf course since the mid 1970s and more recently, has been used to recharge the groundwater system through its East Range Recharge Facility, a MCA project constructed in 2001. A recent upgrade to the golf course’s irrigation system and conversion to a desert-style course (i.e., reduced fairway widths and overall irrigated turf footprint) allows the course to use roughly half the water of comparable golf courses in the region. The saved water is then available for recharge.

Capitalizing on a multi-year Army-wide whole neighborhood revitalization program, Fort Huachuca has been able to save an estimated 200 acre-feet/year through installation of xeric landscaping and water efficient plumbing fixtures in new Military Family Housing (MFH) units.

Through partnership with The Nature Conservancy and cooperation with other federal agencies, Fort Huachuca has been able to purchase conservation easements on over 5,200 acres of land. These conservation easements, which enhance mission viability by maintaining open space on adjacent ranches and retire agricultural land use, reduce current and future water use by an estimated 1,400 acre-feet/year. Funds for these conservation easements were either locally-derived Army funds, from grants from the Arizona Military Installation Fund program, or obtained through the Army Compatibility Use Buffer (ACUB) program. These easements also ensured the post could sustain and increase the use of its restricted air-space and have the capability to support four Predator Class UASs, all Shadow training for the US Army and Marine Corps, Army and Joint C4ISR testing, two Air Force Wings, and the Air Guard Combat Assault Training Center.

Fort Huachuca is a founding member of a consortium of 21 agencies and organizations working together to achieve sustainable yield of the area’s groundwater resources. The purpose of this consortium, known as the Upper San Pedro Partnership (USPP), is to coordinate and cooperate in the identification, prioritization, and implementation of comprehensive policies and projects to assist in meeting the region’s water needs including those of the San Pedro River. Through the USPP, Fort Huachuca has contributed to community-wide programs to reduce groundwater use including participation in the USPP Water Conservation Business Grant Program. This program funds water conservation improvements in area schools and businesses with recurring water savings of over 20 acre-feet/year.

Other USPP efforts have resulted in substantial water savings, including the funding of a reclaimed water distribution system for a community golf course with 300 acre-feet/year of treated effluent, and the funding of a sewage treatment and recharge project to replace an evaporative sewage lagoon. It is important that partnerships like this with your outlying communities are fostered as an integral part of your overall water management strategy.

Monthly and annual progress reports are published in the fort and local city newspaper, and announced on local radio stations. Education and technology development are installation-wide, engaging the 54 tenant organizations, the elementary and middle schools and the families of military personnel living on the fort. Many practices within the GRMS extend to the surrounding community through partnerships that support or are supported by the USAG-HUA. USAG-HUA has helped export these practices into the larger watershed with our USPP government and land management partners. The partnership exemplifies the Army Community Covenant and embraces a holistic approach to water sustainability. Many elements of the GRMS are exportable to other installations.

These environmental benefits are both actual realized gains in water savings and environmental stewardship that put the Army at the forefront of water sustainability. The practice has resulted in a 60 percent reduction in the annual groundwater pumped in 2010 versus 1993, more than 410 million gallons of conservation. The energy to pump this water would have added more than $2.4 million to our 2010 funding requirements. This reduction has allowed Fort Huachuca to reach the net zero position for water use — we reduce, capture, reuse, or recharge more water than we consume.

Where do we go from here? We have more projects on the books, including additional stormwater capture with reuse or recharge projects and exploring facility net-zero concepts for new and existing buildings. We continue to require education of incoming Soldiers, Civilians, and Families. We continue to survey the environment for technology that will bring reasonably priced water use reductions to Fort Huachuca. Net zero is not the end of our requirement, just a spot to stop and audit what we have accomplished and look forward to ensuring we can stay here through the many changes to the Army at War.

References:

http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/21494919/ns/us_news-environment/ , Associated Press, 10/27/2007

http://www.energybulletin.net/53777 , Published Aug 12 2010

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Engineer Research and Development Center (ERDC)/Construction Engineering Research Laboratory (CERL) Army Installations Water Sustainability Assessment: An Evaluation of Vulnerability to Water Supply, Jenicek, et.al, September 2009

Army Water Resources Plan, Fort Huachuca Directorate of Public Works, Environmental and Natural Resources Division, April 2009

Comprehensive Energy and Water Management Plan, Fort Huachuca Directorate of Public Works, Engineering Plans and Services, April 2010

This article was originally published in the 2011 Spring Edition of the U.S. Army Journal of Installation Management.